May 2, 2018 WSU Tri-Cities team researching use of fungi to restore native plant populations

By Maegan Murray, WSU Tri-Cities

RICHLAND, Wash. – A team at Washington State University Tri-Cities is studying how to transplant fungi to restore native plant populations in the Midwest and Northwest.

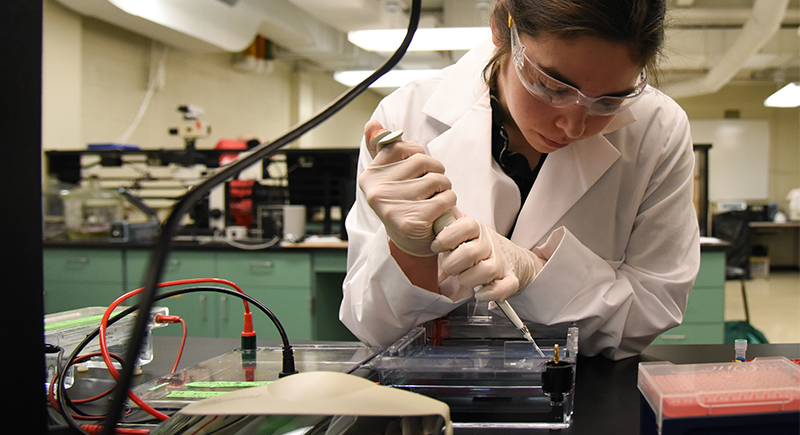

Undergraduate student Catalina Yepez prepares a DNA sample in a lab at WSU Tri-Cities.

Mycorrhizal fungi form a symbiotic relationship with many plant roots, which helps stabilize the soil, conserve water and provides a habitat for many birds and insects, said Tanya Cheeke, assistant professor of biology. Some native plant species are more

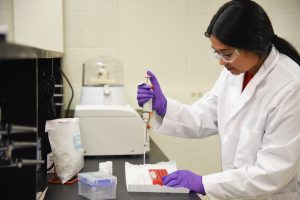

Biology professor Tanya Cheeke works in her lab at WSU Tri-Cities.

dependent on mycorrhizal fungi than invasive plant species are, so when that fungi is disturbed, native plants may not be able to compete as well with invasive species, disrupting the natural ecosystem of the environment and inhibiting many natural processes, she said.

“One way to improve native plant survival and growth in disturbed environments may be to inoculate seedlings with native soil microbes, which are then transplanted into a restoration site,” Cheeke said. “We’ve been doing prairie restoration in Kansas for the past two years. Now, we’re also doing something similar in the Palouse area in Washington.”

Cheeke is working with a team of undergraduate and graduate students to complete the research. A group of her undergraduate students recently presented their project during the WSU Tri-Cities Undergraduate Research Symposium and Art Exhibition. Those students include Catalina Yepez, Jasmine Gonzales, Megan Brauner and Bryndalyn Corey.

The undergraduate team spent the past semester analyzing the spread of fungi from an inoculated soil environment in Kansas to see how far the fungi had spread

Undergraduate student Bryndalyn Corey works in a lab at WSU Tri-Cities.

into a restoration area. One year after planting, soil samples were collected at 0.5 meter, 1 meter, 1.5 meters, and 2 meters from the site of the inoculation in each plot. The samples were then tested for the presence of fungal DNA to see if the mycorrhizal species that they had inoculated with had reached the various distances from the inoculation points.

“The results will be used to inform ecological restoration efforts aimed at improving the survival and growth of native plants in disturbed ecosystems,” undergraduate student Megan Brauner said.

Cheeke said they are also looking at how microbes change across gradients of disturbed environments compared to pristine environments.

“We want to determine the microbes that are present in pristine environments, but are missing from disturbed sites,” she said.

Eventually, Cheeke said they would like to develop soil restoration strategies that other people can implement in their own environments.