September 15, 2017 WSU Tri-Cities engineering and art partner to create robot that interacts with environment

By Adrian Aumen, WSU College of Arts & Sciences

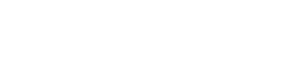

In a cold, dimly blue-lit room, a strange human–animal hybrid paces before the entrance to a fiery red cave. When the “Huminal” senses a viewer approaching, it stops, turns its head to stare at the visitor and emits its own red-hot glow. The viewer must then decide how to respond to the apparent challenge: continue toward the creature or retreat.

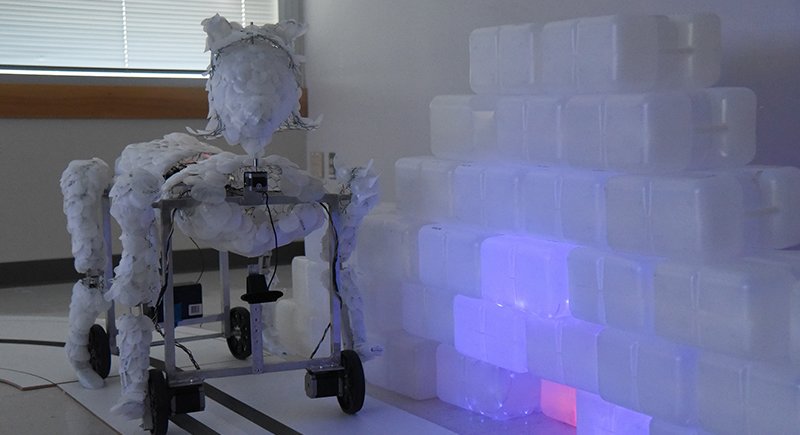

WSU Tri-Cities fine arts professor Sena Clara Creston and engineering student Gordan Gavric work on the “Huminal,” an interactive robot that responds to its environment.

The Huminal is an interactive, kinetic sculptural installation featuring an autonomous, mobile robot that senses and responds to changes in its environment. Created by an interdisciplinary team at Washington State University Tri-Cities, it incorporates research and techniques in fine arts, design, electrical and mechanical engineering and robotics to provide a unique platform for exploring the relationship between humans and machines—and, it turns out, between artists and engineers, too.

Two years in the making and nearing completion this month, The Huminal is the third and most complex art-machine designed and built in as many years by fine arts professor Sena Clara Creston in collaboration with WSU engineering students and faculty. It debuted recently to rave reviews at a robotics exposition for employees of Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Richland, where Gordan Gavric, a key member of the Huminal development team, is an electrical engineering intern.

“The feedback we’ve gotten so far is really great,” said Gavric, a senior in engineering and president of the WSU Tri-Cities Robotics Club. “People recognize it’s a robot, but at the same time they’re a little creeped out. How do people want to interact with a creepy robot?”

Designed to pique curiosity along with uneasiness, the Huminal is about the size and shape of a large dog and covered with white plastic discs resembling scales or fur. Its four jointed legs give the appearance of walking as it rolls in an elliptical path outside its apparent den.

Multiple internal sensors, a camera and a small Raspberry Pi computer communicate with microcontrollers across two electronic systems to direct the robot’s movements and trigger the pulsing red LED lights in its chest. The steady hum of its heart—two 8.6 volt motors—is interrupted only when a sensor detects nearby movement. At that point, the Huminal is programmed to stop in its tracks, turn its head to face the approaching object and transmit its warning glow.

“I look forward to seeing how more people react to it,” Gavric said. “Is it alive? Is it human? The mystery is unnerving and it’s this uneasiness that Sena is trying to exploit.”

A corporeal experience

A new media artist, Creston builds interactive art-machines to create a corporeal experience for viewers. Her artworks invite people to engage with machines and familiar materials in unfamiliar settings and ways. Environmental impact and social consciousness are frequent themes.

WSU Tri-Cities fine arts professor Sena Clara Creston and engineering student Gordan Gavric work on the “Huminal” at WSU Tri-Cities.

“Some people get really aggressive with the work and some are really careful with it,” she said.

By enabling viewers to choose their response to her art, she hopes to help them understand other ways they affect the wider world.

From the haunting Huminal to the satirical Machinescape—an immersive environment of post-consumer electronics—to the dreamlike Umbrellaship—a land-roving, steampunk-style sailboat—much of Creston’s art employs fantasy while exploring intersections between the natural and the man-made.

“Part of it is movement, part of it is response, part of it is material and part of it is social engagement,” she said.

She will talk about her innovative artwork at 1:00 p.m. Saturday, Sept. 16, as part of TEDxRichland events at Uptown Theatre in Richland, Washington.

To create the Huminal’s skin, Creston cut up dozens of discarded plastic water bottles—familiar and somewhat controversial objects that connect the organic and inorganic.

“Many people across the world live with an unsafe water supply, yet we think of water as the source of life and the source of health and wellbeing, and water bottles deliver that,” Creston said. “However, the water bottle itself is not biological or biodegradable—it’s inorganic and it’s not going away. So the material itself becomes this questionable component.

“How do we actually feel for the inorganic and how do these things elicit responses?”

Collaborating in uncommon opportunities

Giving form to Creston’s layered ideas and complex inventions often requires more technical skills than she possesses. So for the past 10 years, she has been learning and implementing modest means of physical computing and mechanical engineering.

WSU Tri-Cities fine arts professor Sena Clara Creston and engineering student Gordan Gavric observe the “Huminal” as it interacts with its environment.

“But, as my mentor explained, I didn’t need to learn how to do everything—I needed to learn how to collaborate,” she said.

Fortunately, interdisciplinary collaborations are strongly encouraged and available at WSU. Engineering professors Changki Mo at WSU Tri-Cities and Charles Pezeshki and Jacob Leachman at WSU Pullman recognized the uncommon opportunities Creston’s projects offered their students and wove them into their coursework.

“Her projects presented the perfect combination of an interesting customer, an achievable design and the monetary scope to take some risks in a shared learning experience,” Pezeshki said.

Students in Pezeshki and Leachman’s junior-level design classes worked remotely with Creston to create The Umbrellaship and Machinescape. The installations were designed, like The Huminal, to question the relationship between humans and their perceived environment.

Eric Loeffler, a May graduate in engineering who constructed the Huminal’s aluminum frame, said he and other students on the project gained a variety of valuable hands-on experiences not usually available to undergraduates.

For example, Loeffler learned new design software applications that he can use in his master’s degree program, and he expanded his welding skills to include aluminum materials.

“There were a lot of new things to work with from an engineering standpoint, and getting the chance to interact with Sena as a client was huge, too,” he said. “There’s really not a class that teaches you how to interact with a person who has their own particular wants, ideas and capabilities. That experience will definitely be useful in the future.”

Shared purposes, different approaches

“Some people might think engineering and arts are very different, but artists and engineers kind of have a shared purpose,” Gavric said. “They create things. They bring things into existence, and have ideas and concepts that they want to make. The difference lies in medium and motive. An engineer might design a circuit board to save a life, while an artist might paint a picture to change a life.”

“Working with Sena, I kind of opened up to ‘why are we doing this this?’ Oh, it’s for the aesthetic, or it’s for trying to get the point across.”

Gavric admits, “There’s no way I ever thought I’d be working on a robot for an art project.” But even before Creston finished presenting her concept sketches to the Robotics Club, he was hooked.

“It intrigued me immediately as an interesting concept and totally something new. There was a lot of back and forth on what we could do with the given technology and funding, and a lot of compromises, abstractions and problems that were solved. It was a rare opportunity. I’m glad I did it.”

Loeffler especially appreciated the chance to think outside the box.

“I really enjoyed the opportunity to collaborate and come up with different ways to solve a problem,” he said. “I think we’re fairly close to what Sena originally envisioned, with the aesthetic and the function she was looking for, and that’s very satisfying.”

The interactive art machine projects encouraged the engineering students to consider their role as engineer, inventor, creator and artist, Creston said. As they grew comfortable working on art projects and expressing their own creative ideas, they sought new collaborations with artists and invited them to participate with the Robotics Club.

Some of the rising engineers began working with fine art students on interactive media projects and even created an interactive art installation of their own, called Lux Flux. The large-scale ceiling installation was designed to sense when a viewer entered a darkened hallway and to send a river of light shooting along the ceiling.

“The project was completely collaborative with a fluid crossover between artists and engineers filling in the rolls of conceptualizers, designers and technicians as needed,” Creston said. “It was beautiful to see.”

Creston is now working with a team of mechanical engineering design students to develop their collective senior year project. Her creative and scholarly work has received financial support from the WSU Office of Academic Affairs, the Department of Fine Arts and the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, as well as a chancellor’s seed grant to provide tools and materials and a project grant from Artist Trust.

The interdisciplinary projects align with the WSU Grand Challenges goal of improving education. They further the University’s Drive to 25 efforts by delivering innovative teaching, community outreach and transformative student experience.

Photos and video by Maegan Murray, WSU Tri-Cities marketing and communications