March 21, 2018 The other side of the atomic bomb – retired Japanese teacher shares survival story

By Maegan Murray, WSU Tri-Cities

RICHLAND, Wash. – The design and construction of the world’s first large-scale nuclear reactor at Hanford is often regarded as one of the largest technological accomplishments in recent years.

It led led to a multitude of scientific advancements, from the invention of nuclear energy to power cities, to nuclear medicine, to the creation of a whole new field of study known as health physics. But despite the many positives of the nuclear industry whose beginnings have origins at Hanford, there is a darker side to the story, as well.

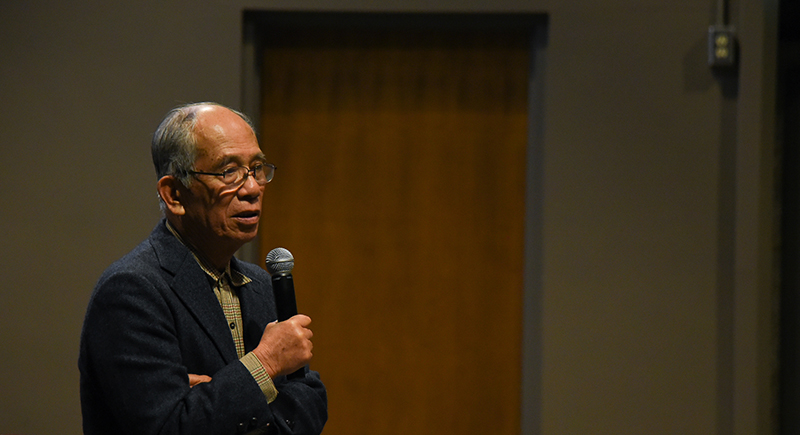

Mitsugi Moriguchi speaks to a packed auditorium at WSU Tri-Cities on his experiences surviving the atomic blast on Nagasaki, Japan, during World War II.

The plutonium created at the B Reactor on the Hanford Nuclear Reservation was used in the atomic bomb that was dropped on the city of Nagasaki, Japan, on Aug. 9, 1945. Nicknamed “Fat Man” for its rotund shape, it was one of the two large-scale atomic bombs dropped on Japan – the other city being Hiroshima. Although the bombings are often regarded as aiding in the end of World War II, the blasts would impact Japanese citizens for generations – emotionally, physically and through the radioactive contamination that would linger for years.

Last month, area residents in the Tri-Cities and Walla Walla heard first-hand from a survivor of the Nagasaki bombing during several presentations over the course of a four-day visit. Mitsugi Moriguchi spoke about his experiences in war-time Japan at Washington State University Tri-Cities and Whitman College, toured B Reactor with a group of colleagues and visited Richland High School. His visit was funded and organized by Consequences of Radiation Exposure (CORE), the city of Nagasaki and Whitman University.

During his presentation at WSU Tri-Cities, Moriguchi talked through a translator about his perspective as an 8-year-old child when the bomb dropped, as well as the lingering radiation that took the lives of many of his siblings and thousands of others.

“Of the seven of us siblings, today only myself and my younger brother are alive,” he said.

Realities from a personal perspective

In the days leading up to the dropping of the atomic bomb on Nagasaki, the city was the scene of incendiary bombings that occurred close to Moriguchi’s neighborhood. As a result, his mother sought shelter for her family kilometers away from their neighborhood.

“During those two days, my family and I crouched in our small area shelter, but don’t think of anything grand and secure like concrete. It was more of a hut close to the ground,” he said.

Nagasaki survivor Mitsugi Moriguchi displays images of the atomic blast on Nagasaki while talking about his family’s experience in escaping the blast during a presentation at WSU Tri-Cities.

They had to leave two of Moriguchi’s older siblings back at their neighborhood as they were required to continue their work in factories at that time. His family anguished about leaving them behind, but fortunately they were reunited when Moriguchi’s mother returned to the scene shortly after the bombing. She found her son with injuries after almost being crushed under a collapse of machinery, as well as her daughter, who had crawled out of a collapsed structure.

Though the family survived the initial blast, their troubles were not over. His immediate family would be plagued by cancer due to the radioactive contamination that occurred in the aftermath of the bombing.

“We managed to survive the immediate impact of the bomb, itself … (but) little by little, the impacts of the radiation got to us and I certainly saw it in cancer,” he said.

Through a collection of photographs, Moriguchi took audience members through what Nagasaki looked like that day. A two-kilometer radius holding a population of thousands was decimated to nothing. Remnants of human remains lay charred in the streets. Thousands of individuals suffered from burns and other extensive injuries who had been near the radius of the bombing.

Moriguchi said he had formerly been criticized for showing graphic images that depicted the realities of that time. He said his intentions, however, were to provide a personal perspective. “I wonder what you think of these images?” he asked of the WSU Tri-Cities audience.

Importance of telling the whole story

WSU Tri-Cities’ Hanford History Project promotes research on and supports community-wide efforts to preserve and interpret the history of the Mid-Columbia. It has a particular interest in the region’s Manhattan Project and Cold War era history specifically because the period was both transformative and complicated, said Michael Mays, director of the Hanford History Project.

Michael Mays (right), director of the WSU Tri-Cities Hanford History Project, and Robert Franklin, assistant director of the Hanford History Project, look through archived newspapers announcing the end of World War II. The Hanford History Project aims to tell the complete story of Hanford.

“The complex issues surrounding the site and its multidimensional impact on world history are part and parcel of the Manhattan Project and Cold War story,” he said.

Mays said what was built at Hanford, and the speed at which it was built, is a testament to human beings’ nearly limitless capacity for imagination. Its developments, however, are also a record of another kind, which detail unintended consequences of human folly oft-repeated, he said.

“So many remarkable things were accomplished at Hanford, seemingly on the fly, but we have to acknowledge the unbecoming realities as well,” he said. “As so often throughout history, the architects of the Manhattan Project were left to ponder the haunting question after the fact: Were we in control of the new technology or was it in control of us?”

When it was established in 2014, the Hanford History Project’s mission was to support community efforts at historical preservation and to collect oral histories from pre-1943 Hanford residents and early Manhattan Project and Cold War workers. Since that time, the project has expanded its oral history program, undertaken management of the Department of Energy’s Hanford Collection, initiated a book series with WSU Press and hosted conferences, seminars and symposia on the subjects.

The Hanford History Project is currently partnering with the National Park Service and the African American Community Cultural and Educational Society to broaden the story of the Manhattan Project by collecting oral histories from African Americans with ties to Hanford and by conducting original research on African American’s experiences of migration, segregation and civil rights at Hanford.

The ultimate goal, Mays said, is to help support the National Park Service in its mission to offer the most comprehensive interpretation of the Manhattan Project possible. Bringing together these varied perspectives, they hope, will help bring about the kind of productive conversations that can further our understanding of this complex historical time, he said.

Stories like Moriguchi’s are important to the overall narrative of the site and its comprehensive interpretation, said Robert Franklin, assistant director of the Hanford History Project.

“These are messy, morally and emotionally fraught discussions and incredibly necessary ones to grow and educate our understanding of the past, our actions and ourselves,” he said. “Mr. Moriguchi’s experience enriches our discussion and helps us understand the Japanese experience and viewpoint through a lens of personal connection.”

Presenting these difficult viewpoints honestly, but also delicately and with grace, Franklin said, will be crucial in the telling and documentation of the whole Hanford story.

“There are different perspectives and we need to hear and acknowledge them to enrich our understanding of the past, and to learn from that past to make better decisions in the present,” he said.