Collections |

Hanford History Project

Welcome

The Hanford History Project (HHP) at WSU Tri-Cities was established in 2014 to foster greater understanding and awareness of the vital role the mid-Columbia region of Washington state–both its people and its environment–has played on the regional, national and international stage from the Second World War to the present day.

In seeking to become a destination for academic research and public education, the HHP endeavors to preserve and interpret the many stories, told and untold, that have shaped our region.

HHP’s research and education functions are especially timely as the National Park Service embarks upon its mission of interpreting what was arguably the defining event of the twentieth century, the development of the Manhattan Project and the production of nuclear weapons. In collaboration with the recently created Manhattan Project National Historical Park, the Hanford History Project’s mission is to help broaden our understanding of that event and its diverse legacies for generations to come.

We want to know: What’s Your Hanford story?

Michael Mays

Director, Hanford History Project

Hanford and the Manhattan Project

Transcript

Robert Bauman: Well, we can go ahead and get started with the interview.

Harold Copeland: Sure.

Bauman: So first I’m going to have you say your name and then spell it also.

Copeland: Yes. I am Harold Copeland, Harold Curtis Copeland, H-A-R-O-L-D C-U-R-T-I-S C-O-P-E-L-A-N-D.

Bauman: All right. And my name’s Robert Bauman and today is August 6, of 2013. And we’re conducting oral history interview on the campus of Washington State University Tri-Cities. And so we’re going to be talking about your experiences working in the Hanford site. So I wonder if we could start by having you tell me first, how you came to Hanford, when you got here, any first impressions of the place, any of that.

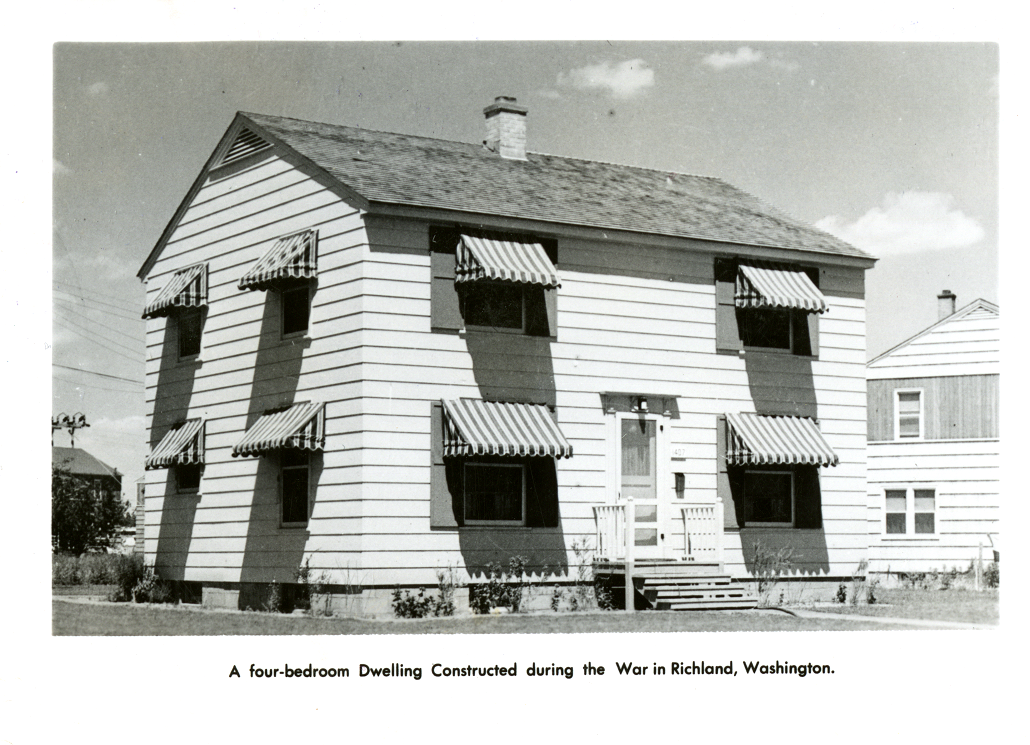

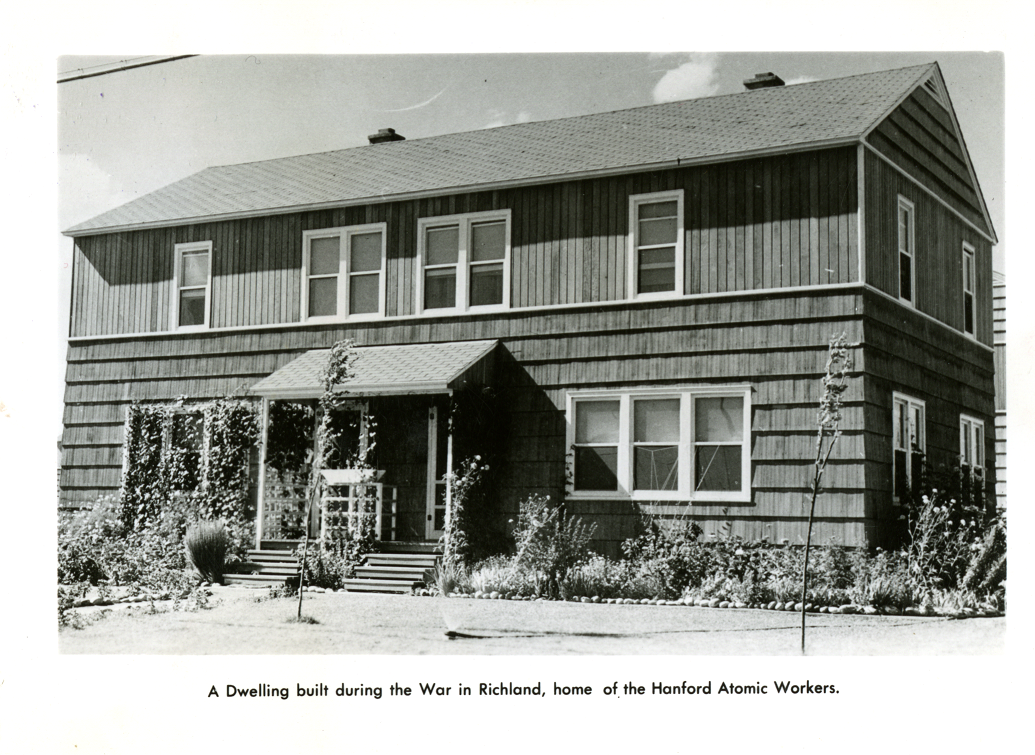

Copeland: My wife and I came here from Denver, Colorado in October 1947. I was working for the Bureau of Reclamation. They were decentralizing their main office, sending people to all the field offices. General Electric came in recruiting and they had received word of this decentralization, looking for engineers. So there were a number of us that thought that’s a good opportunity, so we came out here, 1947. We’re driving our little three-window Ford Coupe and towing my Harley motorcycle on back. And the first impression of Richland was pretty grim. We came into town and all we saw were these flat-topped, prefab houses. They didn’t have their peak roofs yet. And there was dust in the road and not hardly any trees. But we came here. General Electric said there’s a job for five years. Well, for the first four or five years, we kept thinking, when do we go back to Colorado? I grew up in Colorado. See, it’s a neat place in Fort Collins and I graduated from CSU there, so naturally, it was like home. But after five years, we began to like this place. We had the Columbia River, the Yakima River, had the Blue Mountains, the Cascades, and the ocean, and fishing in the ocean not too far away. So we made it our home for all these years.

Bauman: And when you and your wife first came, what sort of housing did you live in first?

Copeland: They were building houses rapidly. The A and B houses, a lot of those were up and people living in them and prefabs, as I mentioned. Our first few months, we were living with Lee Hall and his son, 700 Sanford, in a two-bedroom prefab. And a wife and I got the small bedroom. She was pregnant when we got here. December 7, the Pearl Harbor Day, but in 1947, our first daughter was born and there was pretty cramped conditions with the baby beside the bed and then a two-bedroom prefab, well, the crying at night. She had not gotten used to sleeping at night. But Lee Hall said he had one bad ear. He says, put her out in the living room and let her cry out there. I’ll just turn my good ear down and I won’t hear her. So we did and the crying session and nothing happened from it. Finally got the message to Diane that she was supposed to sleep at night, so that was nice. And Lee Hall was so glad to have a woman in the house to do cooking and do furniture. She did curtains and changing paint and putting a woman’s touch on the house like women can do that men don’t have any idea about. Well, she did that and he was very pleased to have us with us, but they were building the pre-cut houses. And we get in along about in the ’48, it was probably in March or April, the pre-cut houses were ready to be occupied. We moved to a two-bedroom pre-cut. Lee Hall was most depressed and dejected because we were leaving and taking all his good drapes away. So we lived at 700 Sanford for several years until about, I think it was 1973, our second child was born. So on the housing list, we were eligible for a bigger house, a three bedroom. We were in a two bedroom. It so happened I was working with the engineer, Verne Hill was his name. And he lived out on Atkins. And he said, they had a housing list. Big board behind the glass, a housing list was posted. You’d go down and apply for housing that became available. Verne told me his next door neighbor was moving, so I applied for that house before it was posted, see? So I was first on the list of eligibility for the house and we got the house at 209 Atkins because of Verne. And it—they were well-built houses, number one grade lumber, and it’s been a very durable and good place to live over the years.

Bauman: Where was this housing list that you mentioned? Where was that?

Copeland: They had sort of a housing department located in the vicinity, very close to where the Richland Police Department is, across the street from the Federal Building would be. But they would post this housing list and people that were eligible to move would go in and apply.

Bauman: And how would you describe the town of Richland at the time in the late ’40s and early ’50s? What kind of place was it to live?……

News

Feb. 3: Hanford History Project to celebrate Black History Month through kick-off of Civil Rights project

By Maegan Murray, WSU Tri-Cities

RICHLAND, Wash. – Washington State University Tri-Cities’ Hanford History Project will celebrate Black History Month on Saturday, Feb. 3, through a kick-off event for a project that will document African American History at the Hanford Site.

The event, which runs 5 p.m. – 7 p.m. at the Richland Public Library, will feature a 45-minute presentation by speakers from the National Park Service, the African American Community Cultural and Education Society, the Hanford History Project and more.

.... read more

Speakers will discuss the goals of the WSU and National Parks Service civil rights oral history project, the work being done in the community regarding the documentation of African American history in the area, as well as make an announcement of a new survey project taking place in East Pasco regarding African American History. Individuals will also be invited to participate in the oral history project documenting African American life at the Hanford Site.

Individuals will then be invited to mingle, enjoy refreshments and learn more about the civil rights oral history project, as well as set up interviews for the project. Posters displaying life for African American workers at the Hanford Site will also be on display.

The Hanford History Project received a grant from the National Park Service recently to analyze the experience of African Americans at Hanford, as well as research and document African American migration, immigration and settlement before and after coming to Hanford. Hanford History Project staff are looking to interview African American individuals who had some experience of the Hanford Site at the time of the Manhattan Project or in the years after.

“We hope to talk to anyone who worked at Hanford or resided in the Tri-Cities from 1943 up through the late 1960s,” said Michael Mays, director of the Hanford History Project. “We want to understand, in better detail and scope, what the experiences were of these individuals from a personal angle.”

Appointment times will be available for those who wish to schedule oral history interviews and information will be provided regarding scheduling interviews with friends or families not able to attend.

For more information on the event, and to participate in the oral history project, contact Jillian Gardner-Andrews at j.gardner-andrews@wsu.edu, or visit https://tricities.wsu.edu/hanfordhistory/.

WSU Tri-Cities to Partner with Department of Interior, National Park Service to Document African American History for Hanford Nuclear Site

By Maegan Murray

RICHLAND, Wash. – Washington State University Tri-Cities was recently awarded a $73,000 grant in partnership with the U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service to research and document the African American migration, segregation and overall civil rights history at the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, Hanford.

.... read more

Michael Mays, WSU Tri-Cities director of the Hanford History Project, said the African American story and perspective remains largely undocumented and untold at the Hanford nuclear site, which is one of three locations of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park. The other locations of the national park include Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and Los Alamos, New Mexico.

“The history of the science of the Manhattan Project is well known. But the social history, especially with regard to questions of race, class and gender, is much less clearly understood,” he said. “We want to look at and document the settlement and demographic patterns, of the African Americans who were recruited to work at Hanford and then track when and where they migrated to once their employment ended. Hanford in the 1940s, like much of the rest of the country, was an extremely segregated place. This is an important story to tell and an important part of our history that needs to be made known.”

The plan for the project, Mays said, is to examine existing documentation, conduct new research, and interview African American community members throughout the Pacific Northwest in order to better understand the African American experience at Hanford.

“The Hanford area went from a handful of small farming communities comprising a few hundred residents in the early 1940s to a peak population of nearly 50,000 at Camp Hanford in the course of fifteen months,” he said. “There are many stories of the African American experience at the Manhattan Project and we want to be able to share those stories from these individuals’ perspectives.”

The completed interviews will be included with the WSU Tri-Cities oral history collection of the Hanford Site, as well as displayed and made available through the National Park Service, and at the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, Hanford.

Mays said they are looking for African American individuals or their family members who had a role in the Manhattan Project at Hanford and with the site before, during and after the Cold War, or were related to the site in any way during those times. Those who are interested should contact Jillian Gardner-Andrews at 509-372-7447 or j.gardner-andrews@wsu.edu.

“We are actively trying to identify people who experienced at first- or second-hand this remarkable history,” he said. “We woud love to hear from these individuals and document their stories.”

Mays said the project will be completed over the course of two years. Interviewees will be identified and scheduled by the end of the year with interviews wrapped up by the end of spring. He and his team will then perform a review of documents and literature available on the subject and write up and publish their findings by the end of their second year.

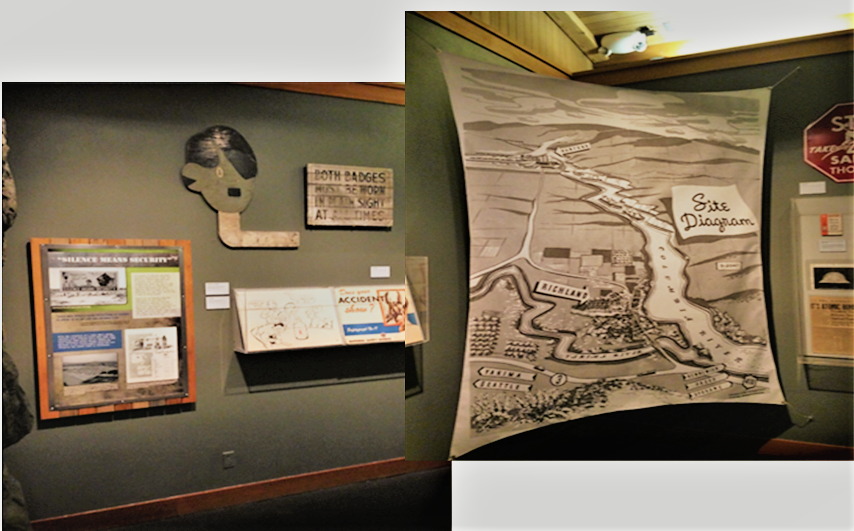

The High Desert Museum Hosts 'Hanford: A Complicated Legacy'

HHP assistant director Robert Franklin visited the High Desert Museum (www.highdesertmuseum.org) in Bend, Oregon, on May 22, 2017 in conjunction with the opening of the museum’s “WWII in the High Desert” exhibition that included artifacts from both the Hanford History Project and DOE’s Hanford Collection.

....read more

“WWII in the High Desert” featured a wide variety of themes including environmental change, Japanese Internment, and the Hanford Unit of the Manhattan Project. Franklin’s talk, “Hanford: A Complicated Legacy,” covered the history of the Hanford site from the pre-1943 towns displaced by the Manhattan Project, the WWII and Cold War era developments, and the current efforts to preserve and promote the natural and historical content of the site. Approximately 60 people attended the talk which was followed by a robust question and answer period. “WWII in the High Desert” ran from May through September 2017.

Preserving and Interpreting Our Past

The Hanford History Project is an archive and curatorial repository focusing on the Hanford site and the Tri-Cities region. We administer the Department of Energy’s Hanford Collection, partner with Northwest Public Television for an oral history project focused on Manhattan Project and Cold War-era Hanford workers, and house numerous collections donated by the community. The Hanford History Project provides academic and historical gateways for students and the general public.

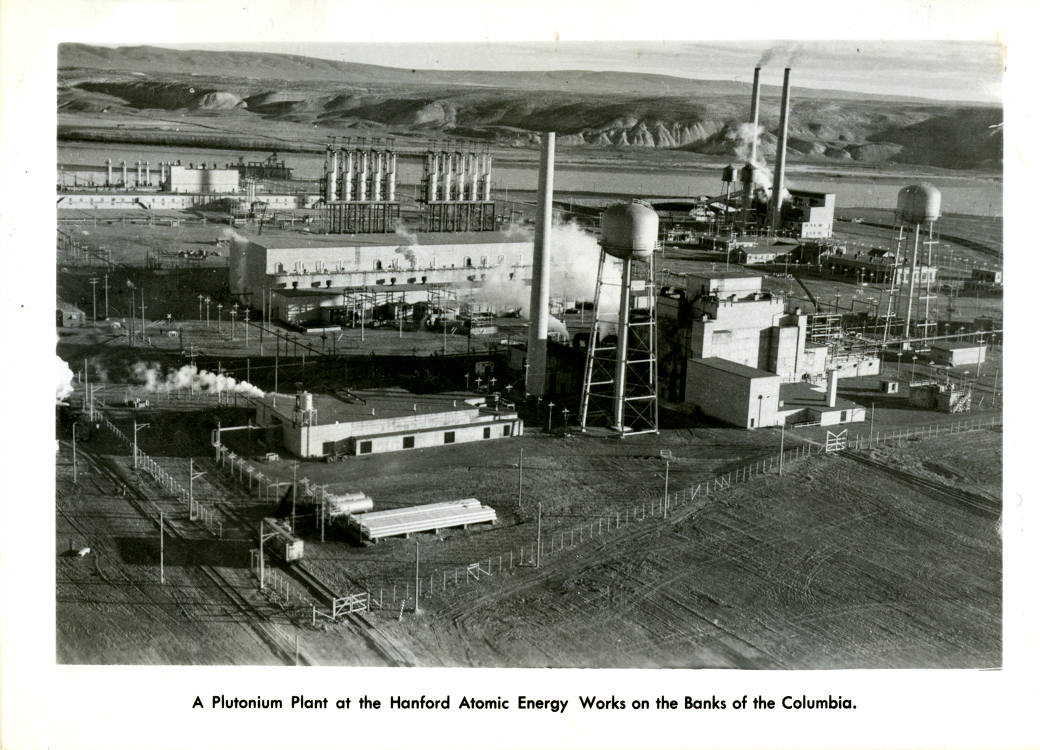

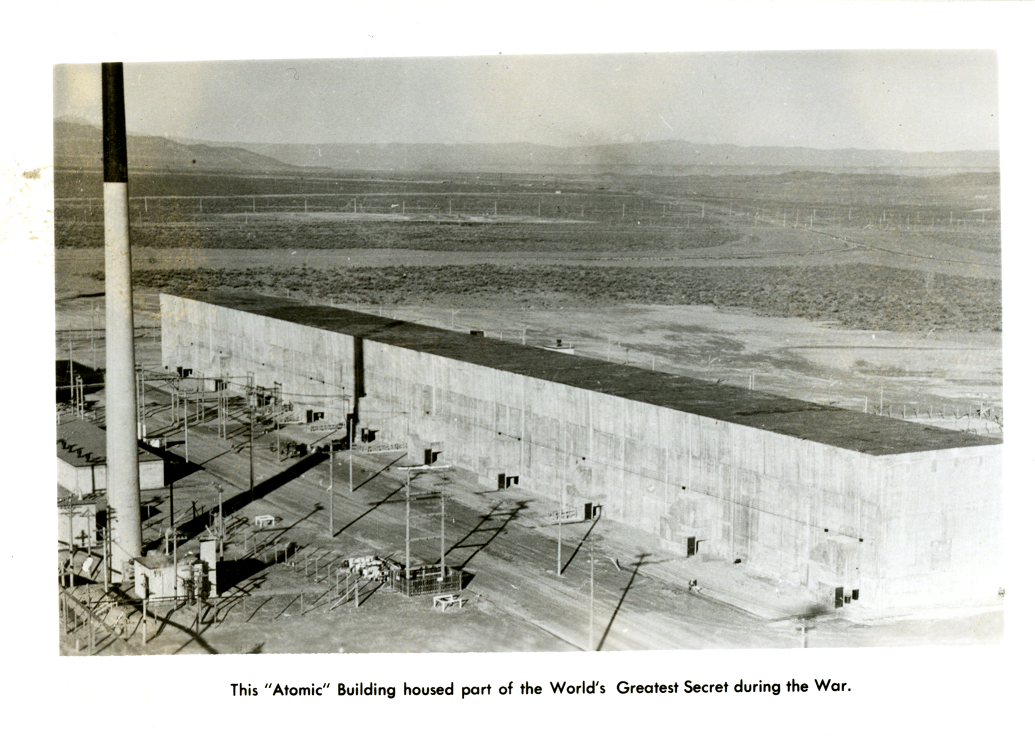

THE HANFORD COLLECTION

“The artifacts, archives, and outreach pieces that comprise the Department of Energy’s Hanford Collection are a material distillation of the defining event of the twentieth century, the Manhattan Project. More even than the Second World War itself, the Manhattan Project and its Cold War legacy altered the course of world history. The Hanford Collection provides a rare and remarkable lens on that event and its complex aftermath, the full effects of which we are only beginning to understand today.”

–Dr. Michael Mays, Director, Hanford History Project

–Photos courtesy of the U.S. Department of Energy